Sports often enjoy the reputation of being egalitarian spaces where athletes are judged by nothing but their athletic merit, but that is a myth. It is especially false in college sports. In reality, they typically exploit their athletes, particularly black athletes, who in many ways assume roles reminiscent of contract laborers – selling their bodies for the opportunity to earn a degree. Becoming a student-athlete may create opportunities that are otherwise inaccessible, but it has not always been a safeguard against the forms of institutional racism experienced elsewhere.

Consider, for example, a scandal that embroiled Sac State’s Athletics Department in 1969. It began with a protest. On November 10, 1969, five of the basketball team’s six black players – Charlie Walker, Jimmie Jones, Jesse Reed, Thurman Lewis, and Leon Sanders – met with their head coach, Jack Heron, and the athletic director, Fred Lewis, to express frustration about systemic racism in the department. Heron and Lewis rebuffed their grievances, and in response, the five players staged a walkout, refusing to return to practice until their grievances were resolved.

As local media caught wind of the walkout, President Otto Butz organized a committee to investigate the allegations of racial discrimination. After a month-long investigation, the committee produced a report. (See a transcription below.)

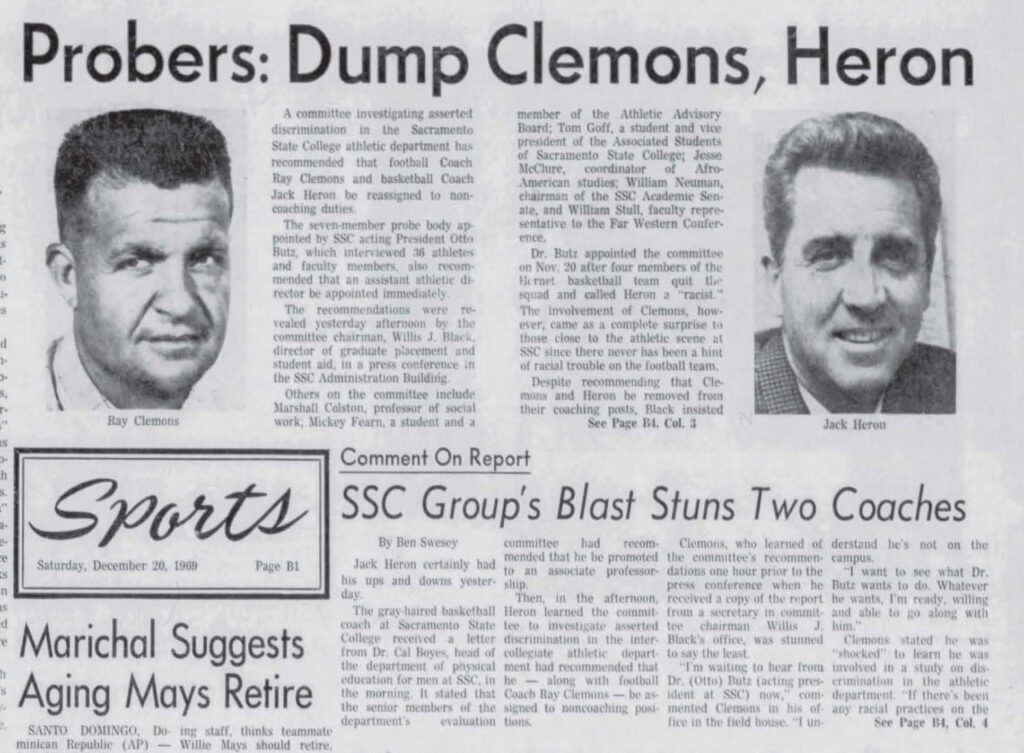

The Black Report, as it came to be known, not only concluded that racial discrimination was a problem throughout the department but also found that both Jack Heron and Sac Sate’s football coach, Ray Clemons, were personally guilty of racial discrimination. It recommended that the university remove them from their coaching positions and that the entire department undergo racial sensitivity training.

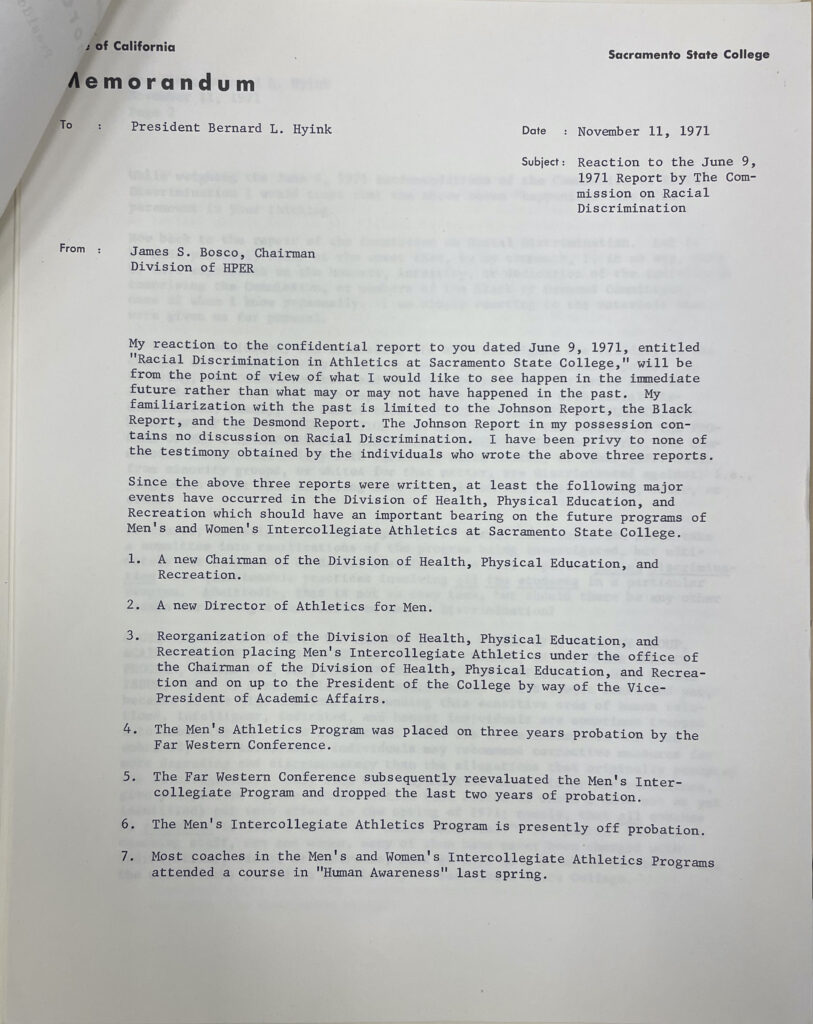

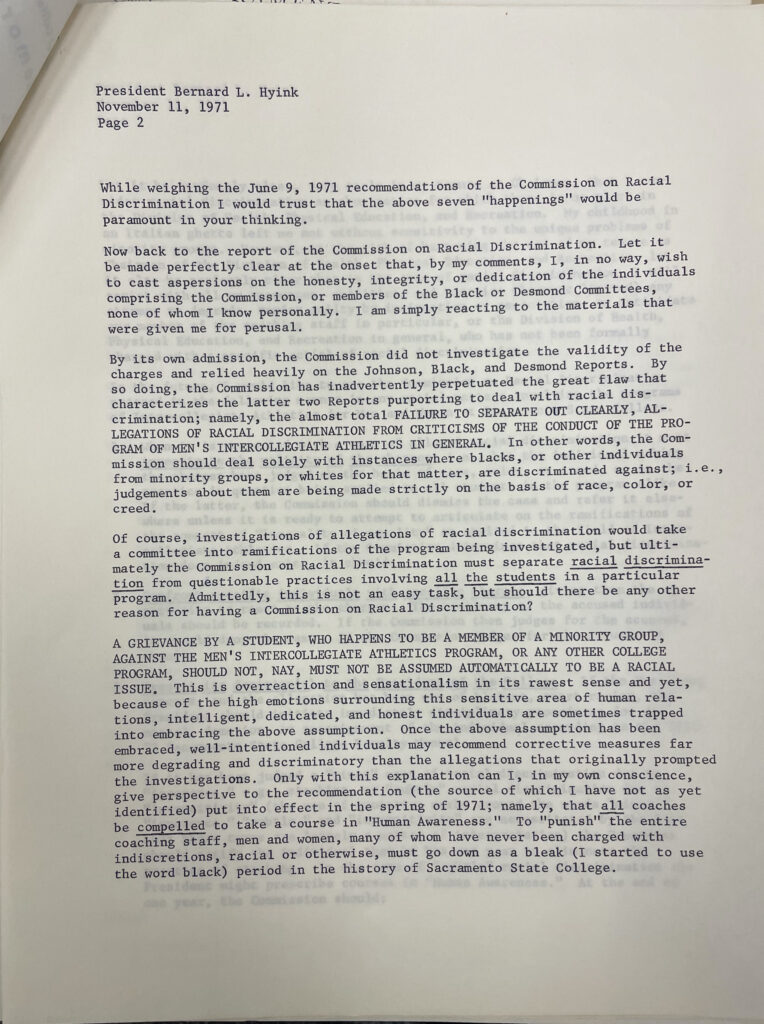

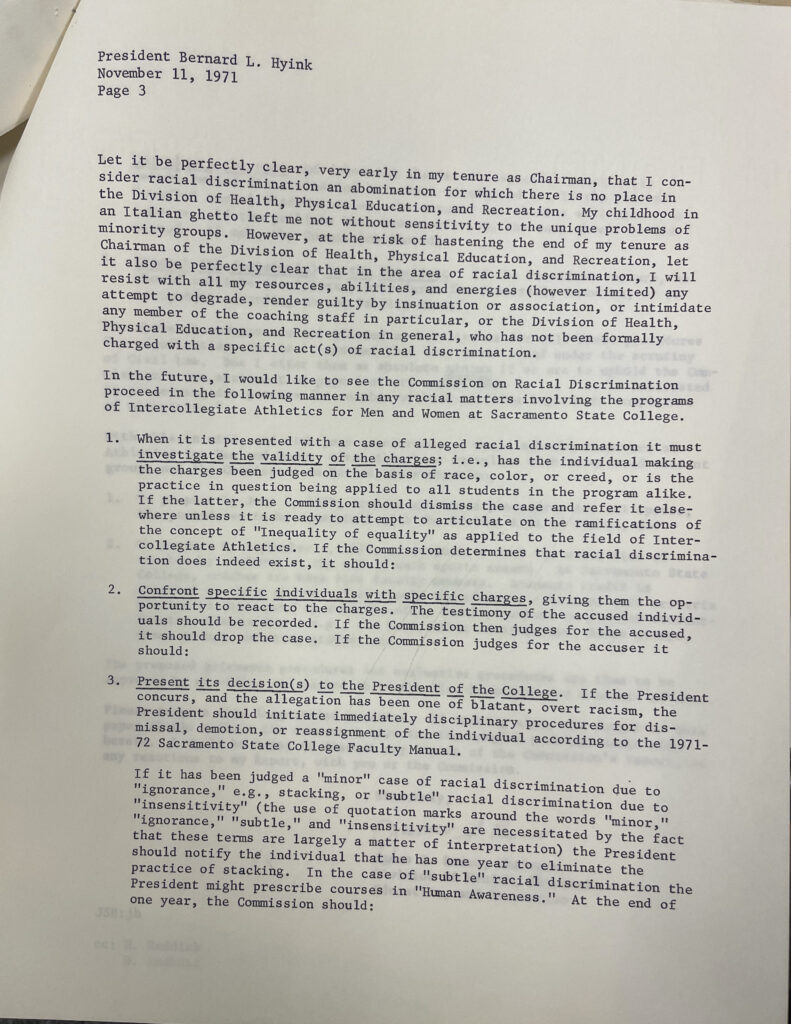

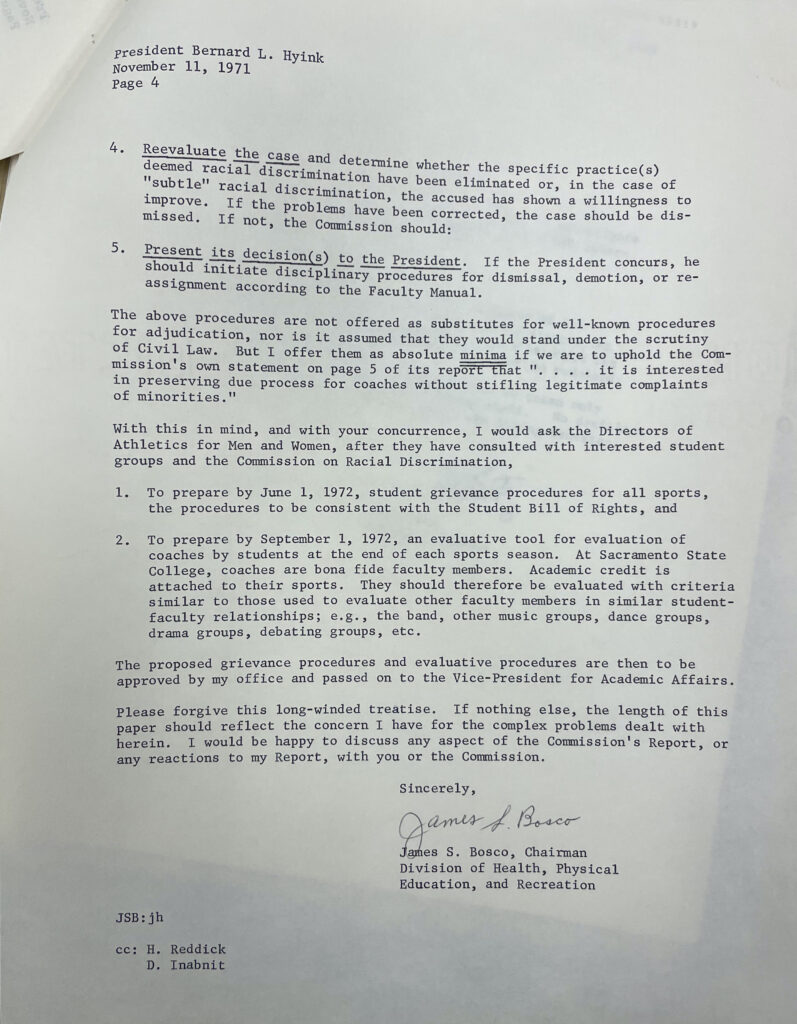

However, although several students, faculty, and staff rallied support for the black players, they were outnumbered by those who refused to accept the Black Report. First came the players, who claimed that the committee was a witch hunt and lacked evidence. Then came the Athletic Department, which voiced total indignation at the report’s findings. Consider, for example, this letter that an administrator wrote to President Otto Butz successor, Bernard L. Hyink in 1971. Bosco’s denial of racial discrimination is hard to justify considering that it followed the Black Report, which gave clear examples of racism.

Nonetheless, Bosco was not alone. President Butz also rejected the Black Report. He organized a second committee to fact check the first, but, likely to his embarrassment, it not only agreed with the first but produced even more damning findings. (See a transcription below.)

An even greater denial, however, came from President Hyink, who wrote to another university administrator in 1971, “it must be understood at the onset that at no time have I been presented with conclusive evidence that coaches or other members of the division of health, physical education, and recreation have practiced overt racial discrimination.”

Asking how could so many individuals could deny a reality that was repeatedly presented with supporting evidence is, perhaps, not a worthwhile question, especially in today’s political environment where we see that facts and empirical evidence so frequently does not factor into how people view events. But we should still ask why Sac State administrators and presidents were so comfortable with denying that racial discrimination had occurred in the Athletics Department. Answering that question would require further research, but we can at least end on one certainty that they condoned racism and that the Sac State community should not let that happen again.

References:

Bennett, Robert A., et al. Black Males and Intercollegiate Athletics: An Exploration of Problems and Solutions. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2015.

Bosco, James S. Letter to President Bernard L. Hyink. November 11, 1971. Series 88. Box 21. “Athletics – Desmond Report, June 1970.” Special Collections. California State University, California.

Bradbury, Steven, Jim Lusted, and Jacco van Sterkenburg, eds. ‘Race’, Ethnicity and Racism in Sports Coaching. New York: Routledge, 2021.

Hyink, Bernard L. Letter to Richard D. Hughes. December 8, 1971. Series 88. Box 21. “Athletics – Desmond Report, June 1970.” Special Collections. California State University, California.

Van Rheenen, Derek. “Exploitation in college sports: Race, revenue, and educational reward.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 48, no. 5 (2012): 550-571, https://doi-org.proxy.lib.csus.edu/10.1177/1012690212450218.

It is sad to think about how there was evidence that there was discriminatory acts by the coaches and yet still the President and others still chose to deny that it happened. Going to Sac state now and seeing how diverse and inclusive it is, I am very surprised that stuff like this happened here but also I feel like it is important to realize how far Sac state has come from this a couple decades ago.

I think this is a dark part of history and seeing this story of discrimination is very hard to read about. Coaches and staff in the athletics department should always be role models for athletes and people in general. As a current Sac State senior I have been proud to say that I have never experienced this type of behavior here. I think it is important to educate ourselves about the past and learn from those mistakes. Sac State has made strides to eradicate discriminatory acts and it is evident today.

It’s really interesting to look at the history of racial discrimination in an institution like Sac State and see such obvious examples of negligence. Today the CSU’s in general seem to be extremely sensitive to any accusations of discrimination so the troubled history is even more surprising. Great job sharing this story, events like this are important to reflect on!