1. The Hornback Case (1975-1976)

One of the more dramatic conflicts between faculty and administration over the years occurred between OG English Department Chair, Vernon T. Hornback Jr., and the Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences, David Ballesteros.

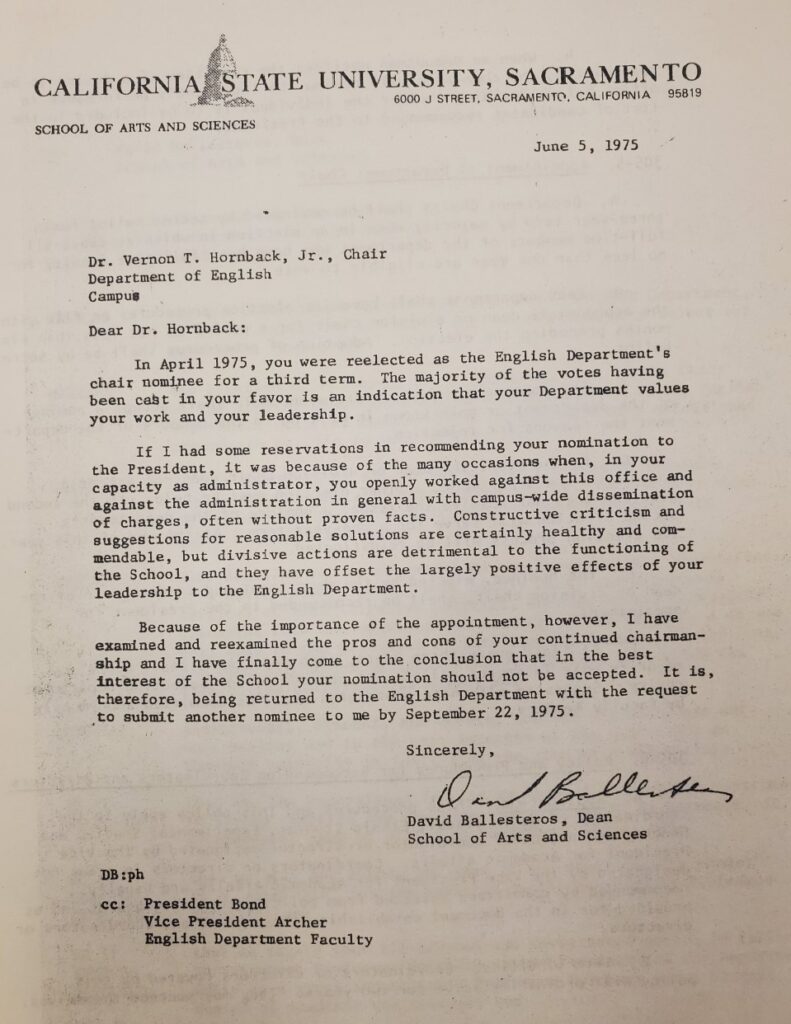

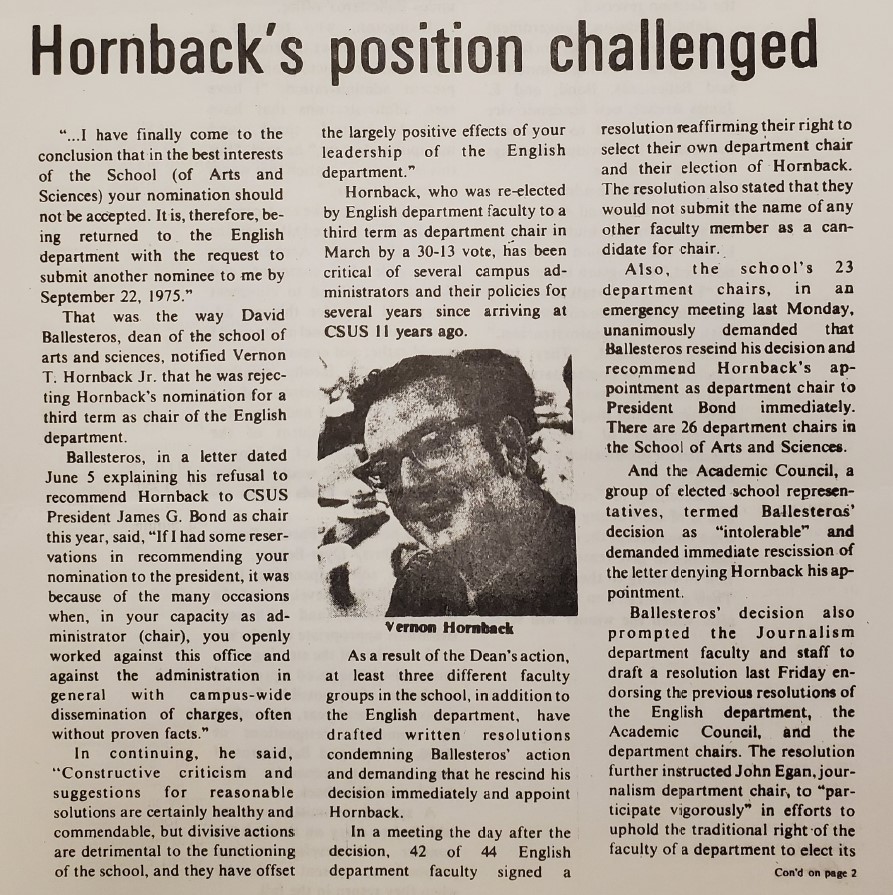

The dispute began on June 5, 1975 when Ballesteros wrote a letter to Hornbeck, who was recently selected for a third three-year term as the English Department Chair, formally rejecting his appointment. “…I have finally come to the conclusion that in the best interests of the School (of Arts and Sciences) your nomination should not be accepted. It is, therefore, being returned to the English Department with the request to submit another nominee to me by September 22, 1975” (Ballesteros Letter to Hornbeck, 1975).

Hornback and the Sac State faculty fought back against this perceived injustice. “The Dean’s letter…makes clear that his action is based on Professor Hornback’s open criticism of administrative policies and practices…The Dean’s action is not the exercise of legitimate administrative prerogative but an overt attack on academic freedom, freedom of speech, and the freedom of department faculties to select their own Chairs” (Executive Committees of the Faculty Senate Memorandum to All Faculty, 1975).

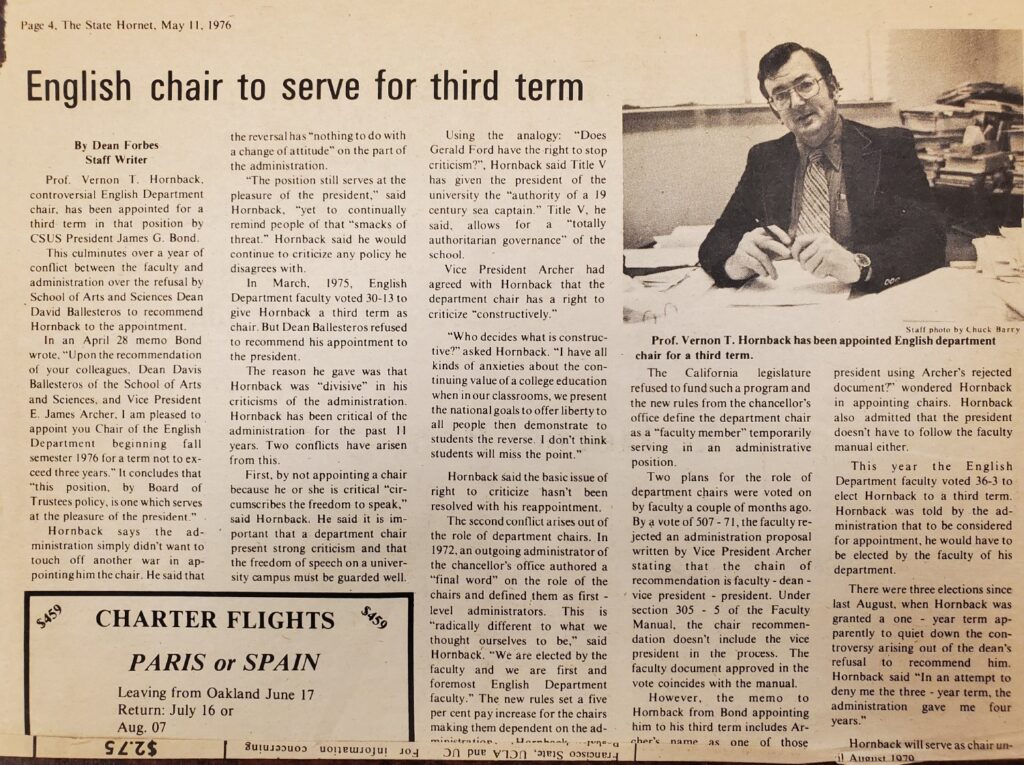

Harsh accusations flew back and forth between the faculty and administration as this conflict extended all through the 1975-1976 school year. Dean Ballesteros, Academic Vice President E. James Archer, and school President James G. Bond initially did not back down either. “Constructive criticism and suggestions for reasonable solutions are certainly healthy and commendable, but divisive actions are detrimental to the functioning of the school, and they have offset the largely positive effects of your leadership of the English Department” (Ballesteros Letter to Hornbeck, 1975).

Hornback refused to yield an inch as well. With the majority of campus faculty supporting his position, he brought a lawsuit against the school. By May 1976, the administration finally relented and President Bond approved Hornbeck’s new three year term as English Department Chair. Hornbeck accepted, but in a gangsta move, he did not drop his lawsuit, requesting $200,000 in damages. “We may very well continue it because it may be an awfully important legal precedent, to wit that the university president must abide by the Bill of Rights” (“CSUS English Chairman Reappointed,” Sacramento Bee, June 3, 1976).

2. Student Strike (May 1970)

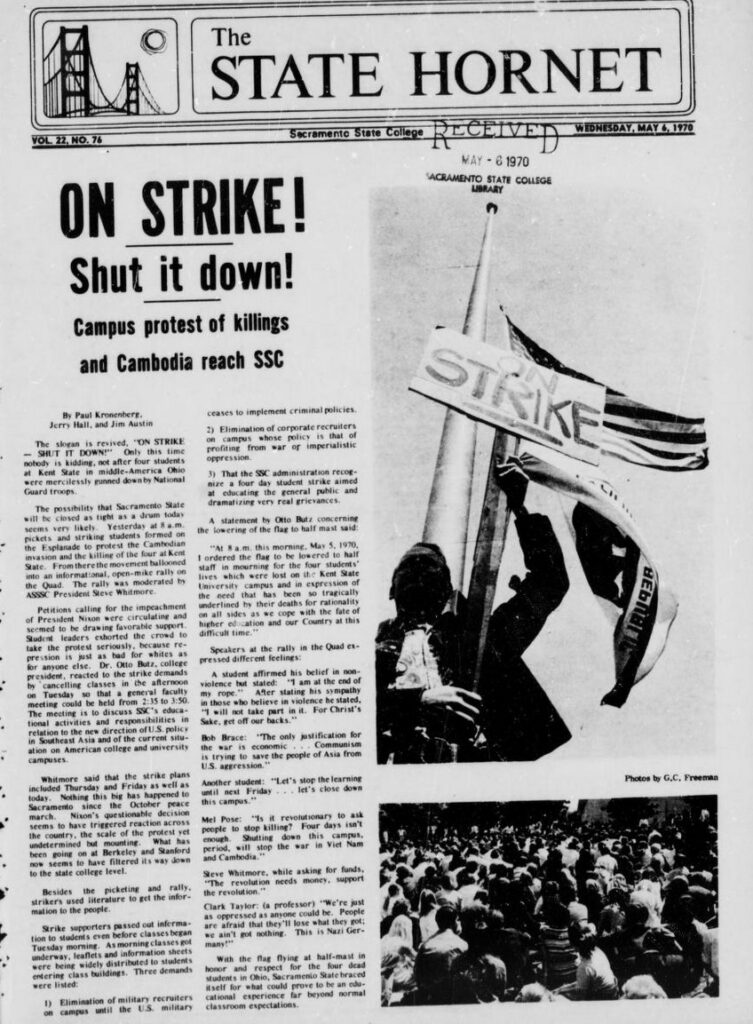

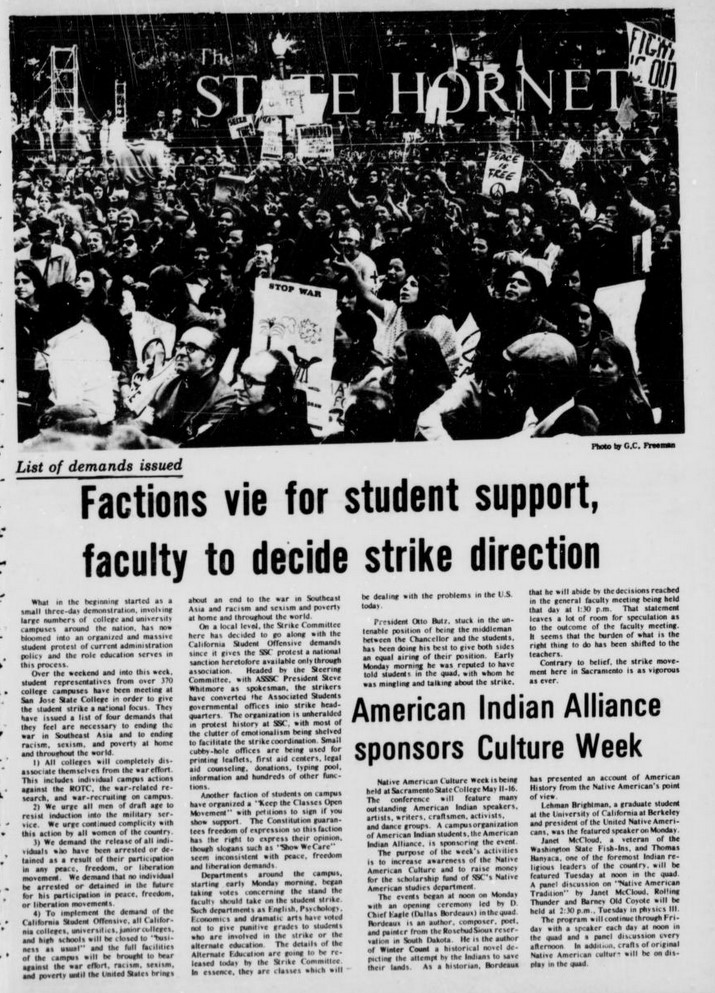

Anti-war protests on college campuses against the Vietnam War were prevalent throughout the late 1960s and grew rapidly into the 1970s as the war escalated. Though demonstrations on Sac State were not as pronounced as on other campuses, one prominent event did take place in May 1970.

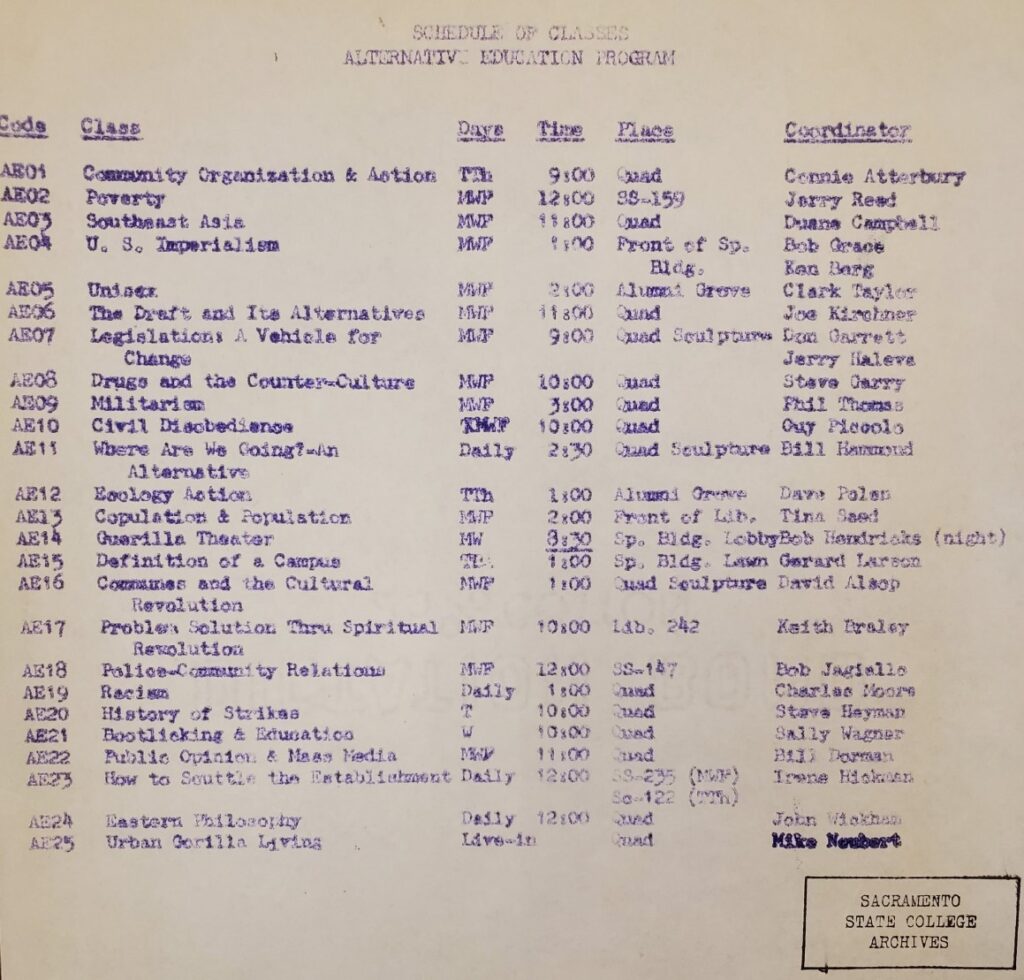

By the fall of 1969, Sac State students became involved with the national Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam movement that was taking place on college campuses nationally. A local campus chapter called the Vietnam Moratorium Committee was formed and organized a series of demonstrations and teach-ins. The teach-ins on Sac State consisted of a series of classes collectively called an Alternative Education Program.

On April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon announced an escalation of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. The next day massive protests erupted on campuses across the country. Demonstrations began as peaceful before gradually turning more violent in response to violence perpetrated by authorities, most notably the shooting at Kent State University on May 4th in which National Guardsmen killed four students and wounded nine and at Jackson State College on May 15th where police killed two students and wounded 12 outside a campus dormitory.

Eventually, Sac State’s protests became more radical as many of the original student leaders and organizations, who advocated for non-violence, stepped away from the demonstrations because they had been taken over by students who were now advocating violence as a means to achieve their objectives.

Over the objections of the Sac State president Otto Butz and other administrators, students and faculty caused the informal shutdown of campus from May 13-15. By May 19, President Butz had accepted two of the three student resolutions. One resolution gave incomplete grades to students who discontinued their current coursework and the other was recognizing the Alternative Education Program classes, giving students credit for one per semester if taken.

3. Society for Homosexual Freedom (1969-1971)

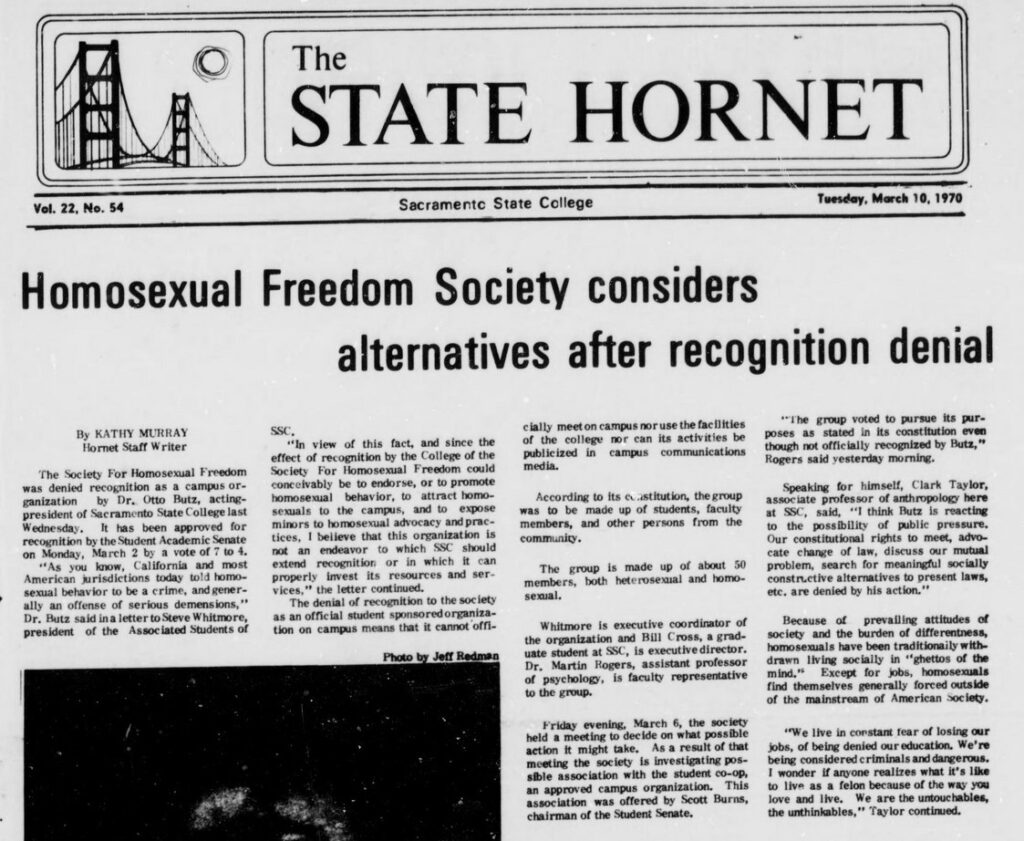

Sac State has come a long way in its support and acceptance of LGBT students, faculty, and staff. The PRIDE Center is an important example of resources for the campus community and has its own interesting history. The struggle for public LGBT acceptance on Sac State began with the Society for Homosexual Freedom.

On the heels of increased African American student civil rights activism in the 1960s and early 1970s, student groups all over the country became active in protesting for recognition and equality. One such group on Sac State was the Society of Homosexual Freedom (SHF), formed in 1970 by twelve students and faculty. Sac State Psychology professor Martin Rogers led the charge, influenced by similar efforts at San Jose State University and University of California, Davis.

The SHF applied for recognition as an official campus group at the Associated Students of Sacramento State College (ASSSC) meeting on March 2, 1970. Following a very contentious debate, filled with objections and insults, the ASSSC approved the petition with a vote of seven yeses, four nos, and one abstention. But the final decision belonged to Sac State acting president Otto Butz, who refused. The ASSSC hired a local attorney and Sac State alumnus, John M. Poswall, and filed a lawsuit to challenge Butz’s decision.

The case was argued at a non-jury trial on October 8, 1970, presided over by Judge William Gallagher. SHF member and ASSSC senator George Raya, testified on behalf of ASSSC that, “We can’t hide and they are wrong.” High ranking school administrators, including former president Otto Butz and current president at the time Bernard Hyink, testified along a similar theme that by recognizing the SHF would imply that Sac State “sanctioned illegal homosexual practices” and that the school would “become a haven for homosexuals” (Reichard, 661). Following months of deliberation, Judge Gallager ruled in favor of SHF.

John Poswall, ASSSC’s lawyer in the case, later remarked that “for a conservative judge like Gallagher to decide the case in SHF’s favor this way perhaps indicates just how important the constitutional claim turned out to be” (Reichard, 662). Sac State formally recognized the SHF as an official campus organization on February 19, 1971.

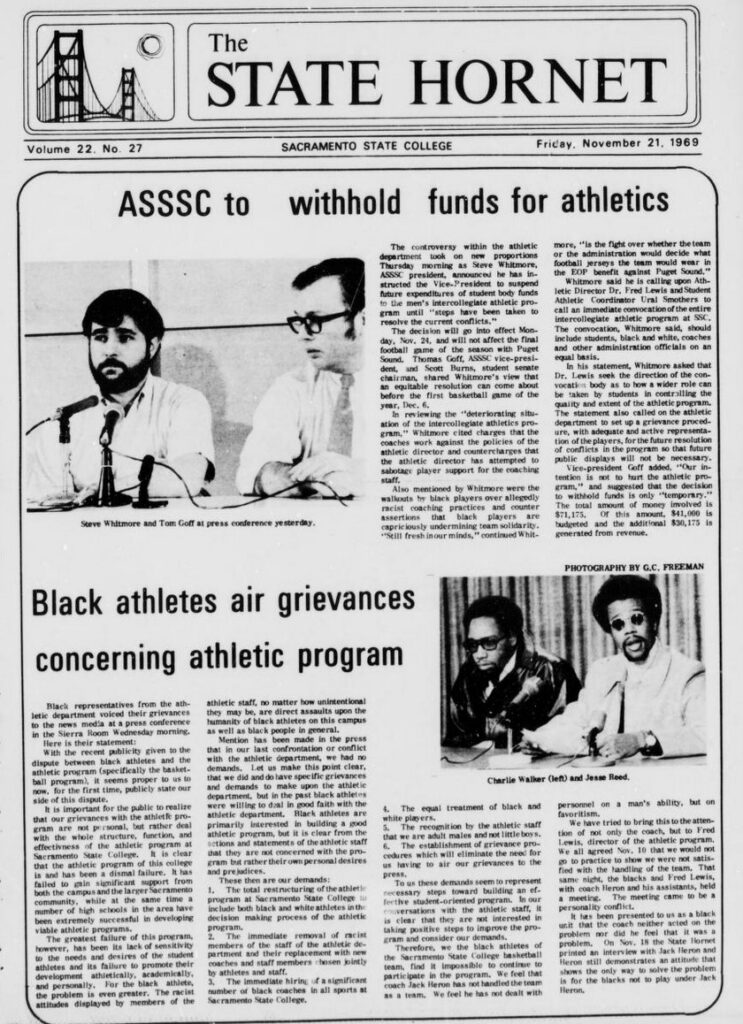

4. Football and Basketball Coaches Accused of Racism (1969-1970)

This controversy started in the fall of 1969 when Black members of the Sac State basketball team brought grievances about their coach Jack Heron to the Athletic Director, Fred Lewis. This fallout from the meeting would end up embroiling not only the basketball program, but the football program as well.

Accusations and counter-accusations were flying all over the place in the local news between players, coaches, and administrators. Two appointed commissions would find corroboration of the accusations but the sitting school presidents ignored their recommendations for improving the culture and work environment of those sports teams. Read a more detailed story in the Hornet Histories post “Condoning Racism.”

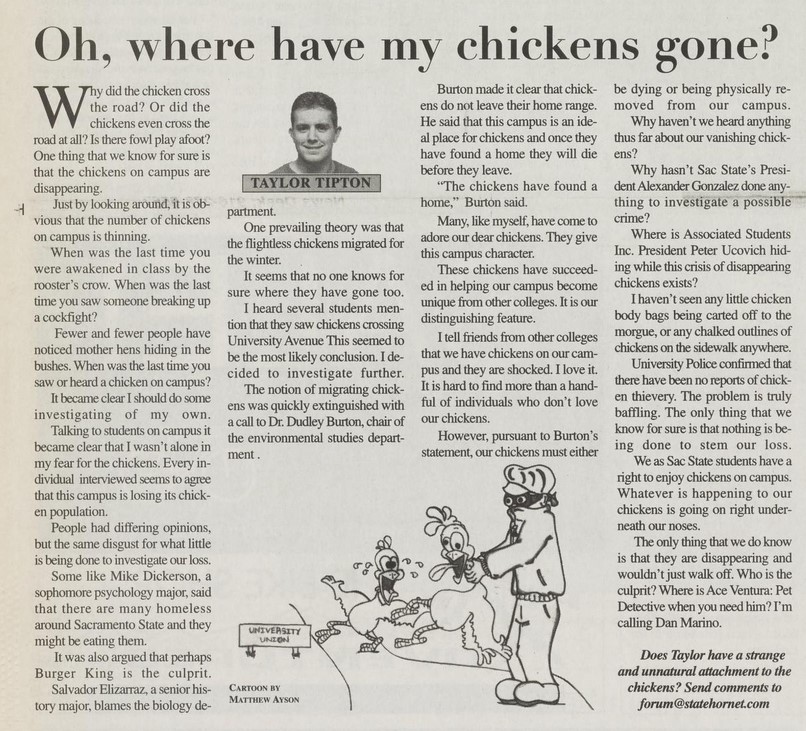

5. Chickens Disappear (2003-2004)

One of the more egregious actions perpetrated at Sac State over the years revolved around the mysterious disappearance of the school’s brood of chickens.

In the later part of the twentieth-century, a group of feral chickens had wandered the Sac State campus for years. No one really knows where they first appeared or how they showed up, but the fowl took on cult-like status among decades of students. The chickens had a live-and-let-live attitude, generally leaving passerbyers alone if they were left alone. But by the time the Fall 2003 semester rolled around, something was not right on campus.

The October 22, 2003 edition of The State Hornet ran two stories about the chickens. Students started taking notice that their numbers seemed to be dwindling unexpectedly. “According to sources in facilities management, there were rumors that President Gonzalez wanted to have the chickens removed off the campus” (“Students Concerned Over Missing Chickens On Campus,” The State Hornet, October 22, 2003). School administration, especially President Alex Gonzalez, remained mum about the subject.

By the next year, The State Hornet ran a story about some facilities staff and faculty taking part in the disappearance of chickens. In the article, it was reported that in a conversation with CSU Chancellor Charles Reed, President Gonzalez told him that he “felt it was time for the chickens to be removed” (“Unofficial Chicken Relocation Program Taken On By Faculty,” The State Hornet, October 6, 2004).

President Gonzalez never publicly came clean as to the disposition of the chickens. Disappointed students across campus were incensed, but were left without any options or answers.

Where did they go? Those with answers were not talking and carried it to their “employment graves.” Most students who cared about the chickens had to sadly move on without proper closure, forever missing this long-time piece of the campus landscape.

6. Vote of No Confidence (2007)

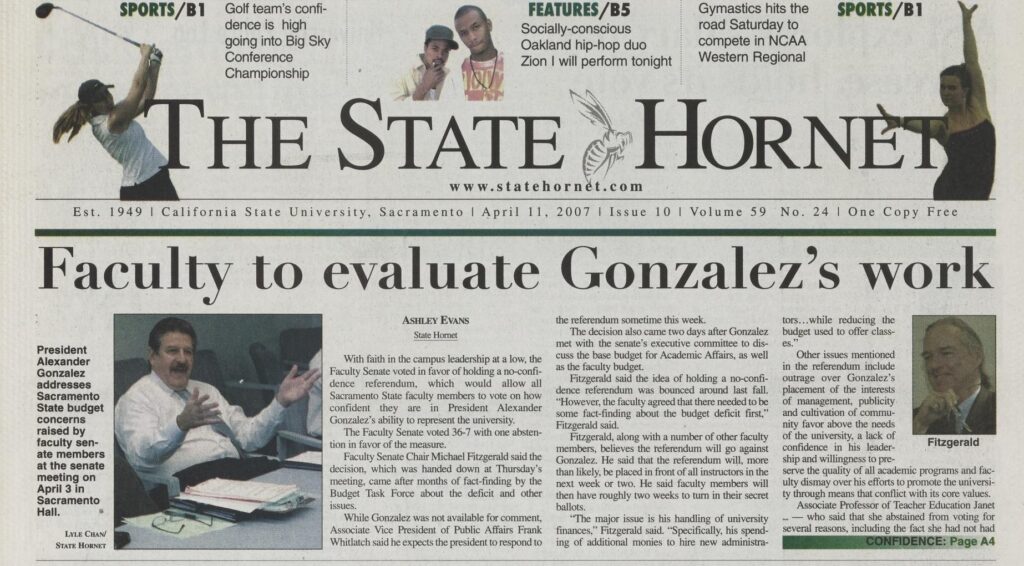

The first decade plus of the twenty-first century saw year-after-year budget tightening for California colleges and universities. Sac State President Alexander Gonzalez was the main target of student and faculty outrage during that period due to a number of questionable budget and leadership decisions.

President Gonzales drew the ire of students and faculty primarily because he prioritized business operations of the school and increased the administration part of the budget pie while class sizes and tuition increased, full-time faculty decreased, and student services were slashed. Sac State faculty felt he was heavy handed in his management style, implementing decisions from the top down. Years of these issues finally boiled over in April 2007 when the Faculty Senate approved a referendum of no-confidence vote against President Gonzales.

The referendum, according to faculty who approved it, “is not to force Gonzalez from his position, but to inform him ‘in the strongest terms possible’ that faculty members want academic programs and classes to be priorities” (“Faculty to Evaluate Gonzalez’s Work,” The State Hornet, April 11, 2007). Though it was noted that previous no-confidence votes at other California State University schools led to their presidents resigning.

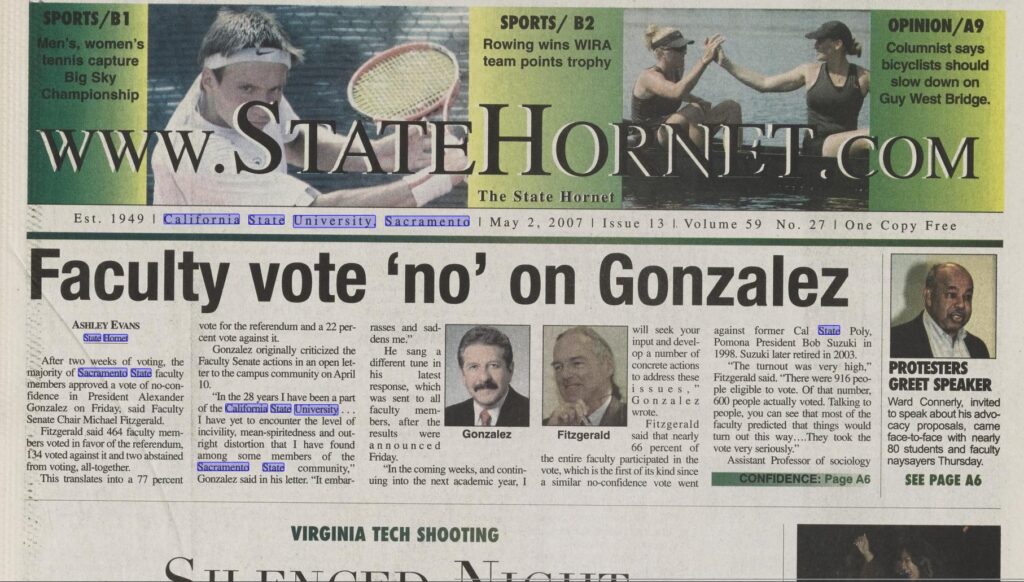

After two weeks, a majority of Sac State faculty members approved a vote of no-confidence in President Gonzalez. 77 percent of those who voted supported the referendum. Gonzalez responded that “in the 28 years I have been part of the California State University…I have yet to encounter the level of incivility, mean-spiritedness and out-right distortion that I have found among some members of the Sacramento State community. It’s embarrassing and saddens me” (“Faculty Vote ‘No’ On Gonzalez,” The State Hornet, May 2, 2007).

Though with continued backing from CSU Chancellor Charles Reed, Gonzalez pretty much brushed off the results of the vote. He had no intention of stepping down and served as Sac State’s president for eight more years until 2015.

7. Fight to Keep ROTC Off Campus (1970s-1990s)

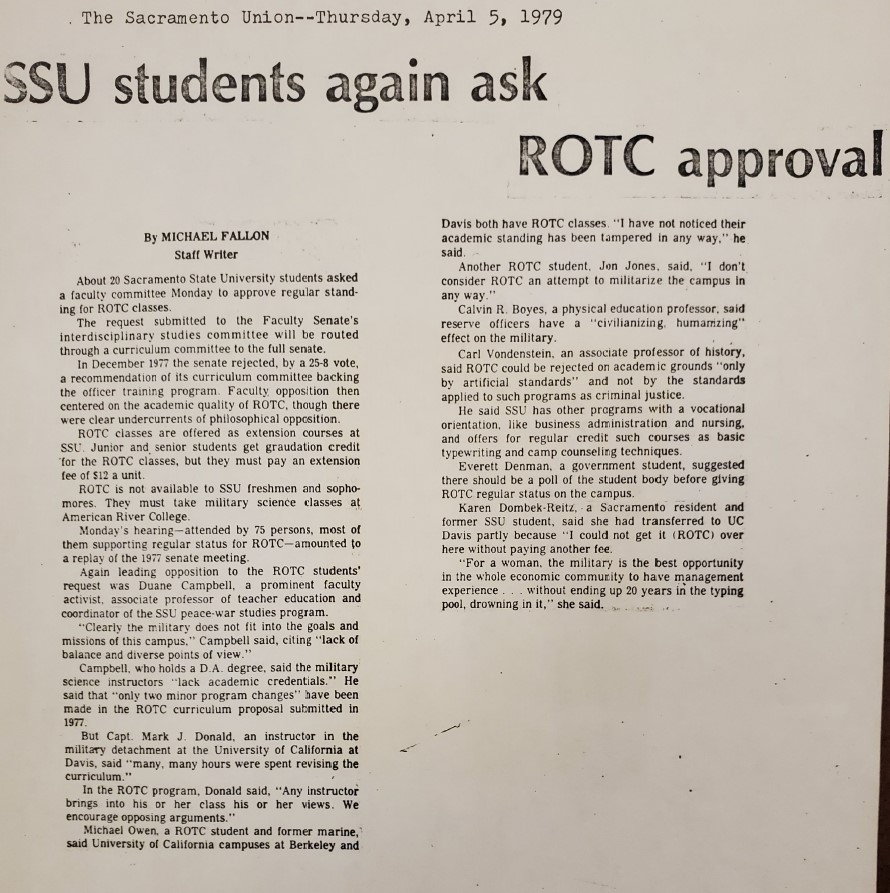

Sac State students wanting to participate in an Army or Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program in the 1960s and 1970s had to travel to University of California, Davis or another campus offering the program in the Bay Area due to anti-war sentiments.

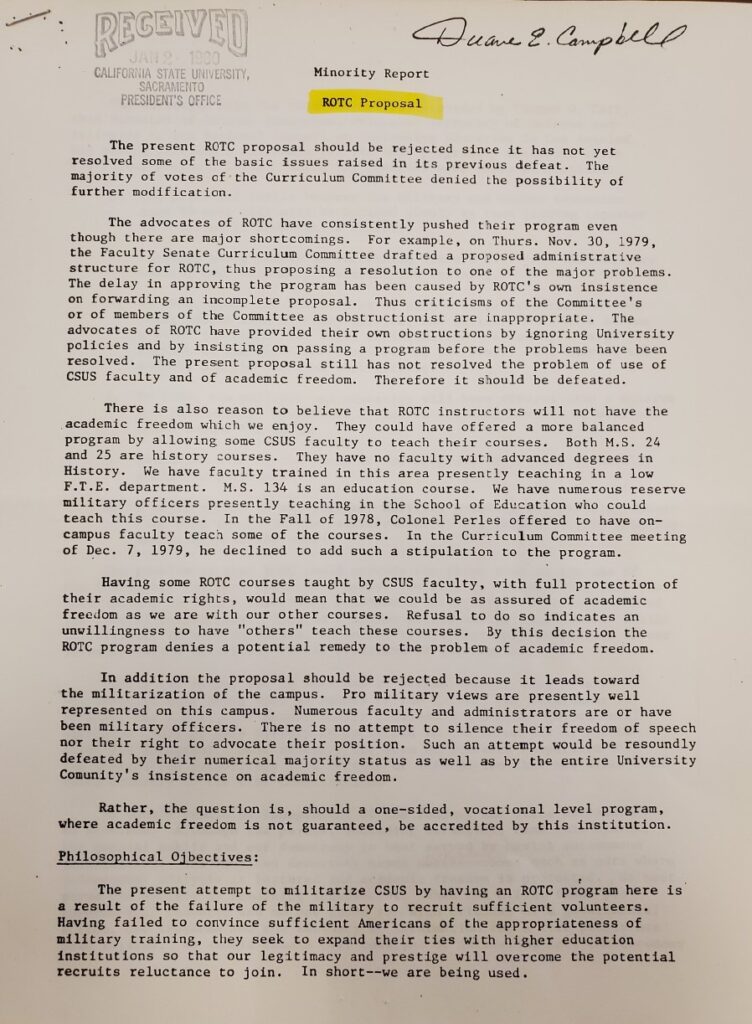

By the mid-1970s, Sac State President James Bond, and his successor, W. Lloyd Johns, were receptive to establishing ROTC programs on campus. Both presidents worked with administrators and the Army and Air Force to make it happen. The effort received considerable pushback from some Sac State faculty and students who still held strong anti-war sentiments.

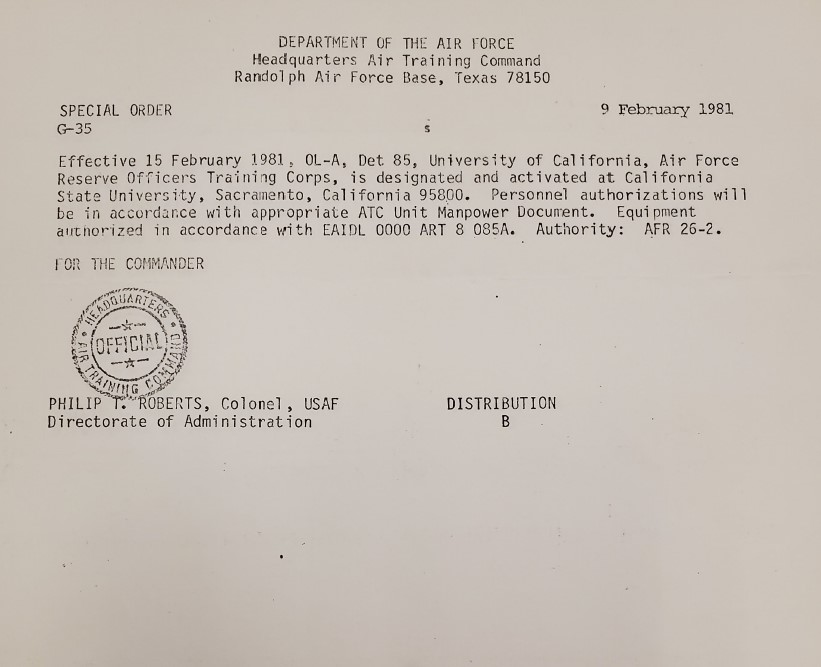

A series of procedural roadblocks put up by the Faculty Senate delayed the actions for a number of years. A vote in 1979 to approve the programs failed, but after renewed efforts by campus proponents, the Faculty Senate narrowly approved establishing an Army and Air Force ROTC program. The programs grew quickly. For example, by 1985, Air Force ROTC enrolled around 200 cadets and the Army program had about 80. Sac State ROTC programs attracted students from all over northern California, including from other college campuses that did not have programs.

Unfortunately on April 22, 1994, after years of deliberation and stalling, President Gerth announced that the Sac State ROTC programs would be kicked off campus in response to the discriminatory practices put in place by the federal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy which banned gay servicemembers from serving openly in the United States military.

By the summer of 1997, Congress threatened the revocation of all federal funds to colleges who kicked off ROTC programs if their decisions were not reversed. Sac State fell in line and the previously banned Air Force and Army ROTC programs were allowed back on campus, but had to build up their presence once again. The two programs continue to thrive today.

8. Parking Fees (1959-1963)

If there is one experience that links all Sac State students from every generation throughout its 75-year history: it’s parking. Parking issues on campus have always frustrated, angered, and caused consternation for students and faculty alike.

Parking has experienced technical difficulties since moving to the current campus site in 1953. At the time the prepared parking spaces were not yet ready, thus early students, faculty, and staff tended to “park where it seemed most convenient – two feet away from buildings, for example” (Moore, 33). Since there was no grass or trees at the beginning, dust clouds were an annoying fact of life, along with fields of mud during the rainy seasons.

As paved parking was built during the first decade, the fight for parking spots was vicious. In 1955, a female graduate student started a one-woman crusade against inconsiderate parkers whose cars took up more than one parking space. “She would print ‘Pig’ or ‘Hog,’ or both, on the trunk of offending cars” (Moore, 45).

Major controversy exploded in 1959 when the State of California started collecting fees to support managing college parking facilities. Sac State pinky-sweared to use the money allocated to them to build multi-tiered parking structures and increase overall capacity. Everyone protested the new fees. Some students argued this was an unreasonable fee for what was supposed to be a free education. Faculty complained it was a tax on their income. Many complained they were paying for other structures to be built at other schools rather than at Sac State.

In 1960, philosophy professor John Linnell brought a lawsuit against the state to prevent collection of the fee. State attorneys argued “this was not a parking fee, but a lease agreement between the president of the college and the auto owner” (Moore, 70). Linnell won an injunction but it only applied to himself. All others were stuck paying the fee. Three years later, Linnell’s case was overturned on appeal giving victory to the state. The fees remained, as do the parking frustrations for everyone through the present day.

Read a deeper dive into the history of parking at Sac State in this fantastic Hornet Histories article, “Parking at Sac State.”

9. Crisis Over Friday Classes (2001-2002)

“If ASI wants war, then it’s war,” Sac State president Donald Gerth is alleged to have told Associated Students, Incorporated (ASI) President Artemio Pimentel during a tense meeting. The cause for such heated words, President Gerth had announced the previous week an intention to change the format of class schedules next school year to include Friday classes.

Prior to the fall 2002 semester, Sac State primarily operated on a four-day-a-week schedule with Monday/Wednesday and Tuesday/Thursday classes. President Gerth proposed that Monday/Wednesday classes, which were 75 minutes long, expand to Monday-Wednesday-Friday (M-W-F), at 50 minutes each. His reasoning was to better utilize campus facilities and allow for increased student enrollment, the latter having been purposely capped over the preceding years.

The proposed changes caused a furor among students and some faculty, many of which enjoyed the flexibility of a four-day week. After months of back and forth meetings and counter proposals, Gerth accepted a scaled back proposal from ASI that would only have M-W-F classes from 9am-noon.

A year later when the new schedule was implemented, even President Gerth’s critics had to admit the new scheduling was a success. It helped relieve overcrowding and increased enrollment.

References:

Donald & Beverly Gerth Special Collections & University Archives, California State University, Sacramento.

The State Hornet. Accessed on Internet Archive. https://archive.org/

Craft, Jr., George S. California State University, Sacramento: The First Forty Years: 1947-1987. Sacramento: The Hornet Foundation, 1987.

Moore, D.E. The History of Sacramento State College: 20 Years of Higher Education. Sacramento: Associate Students of Sacramento State College, 1967.

Reichard, David A. “We Can’t Hide and They Are Wrong: The Society for Homosexual Freedom and the Struggle for Recognition at Sacramento State College, 1969-1971.” Law and History Review 28, no. 3 (August 2010): 629-674. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25701145.

The drama of Sac State was very interesting to read. I will say that the parking fee of 180 per semester is outrageous and should apply for the school year in general. This was a great read. I do enjoy my 50min french class over my longer classes.

Wow I never knew how crazy Sac State used to be back then. It’s cool seeing how far the school has come since the days of protesting about the Vietnam War and racism to whether are not Sac State’s president is a good fit and where the chickens have gone lol. I feel like I haven’t seen the turkeys that were normally out back then, I think that should be a new controversy lol. But in all seriousness, thank you for informing us about the conflicts that most of the public may not know of.